My Frommer’s Guide recommended a stop at the National Museum of Military History in Diekirch, Luxembourg, dedicated to the Battle of the Bulge in the Second World War. It’s hard to imagine, today, that the rolling countryside had seen such fierce fighting: the villages are timeless and unspoiled, set into deep green forests and sunny fields of bright yellow rapeseed. The museum is tucked along the main city street, guarded by an Allied tank peeking from behind an alley, a bit incongruous against the bustling shops and restaurants up the street.

My Frommer’s Guide recommended a stop at the National Museum of Military History in Diekirch, Luxembourg, dedicated to the Battle of the Bulge in the Second World War. It’s hard to imagine, today, that the rolling countryside had seen such fierce fighting: the villages are timeless and unspoiled, set into deep green forests and sunny fields of bright yellow rapeseed. The museum is tucked along the main city street, guarded by an Allied tank peeking from behind an alley, a bit incongruous against the bustling shops and restaurants up the street.

Inside, it first looks like the largest Army Surplus Store anywhere (I think that I actually recognized a flashlight and field shovel that had been handed down to our Boy Scout troop).

Inside, it first looks like the largest Army Surplus Store anywhere (I think that I actually recognized a flashlight and field shovel that had been handed down to our Boy Scout troop).  The curators have collected up anything and everything left behind from the war and filled shelves, display cases, and whole rooms with cascades of artifacts. It’s hard to appreciate the individual pieces, there’s just so much of it.

The curators have collected up anything and everything left behind from the war and filled shelves, display cases, and whole rooms with cascades of artifacts. It’s hard to appreciate the individual pieces, there’s just so much of it.

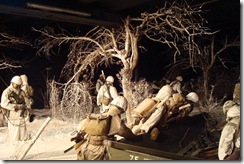

Deeper into the museum, the displays organize into re-creations of scenes from the time, with mannequins dressed in old uniforms and surrounded by everyday things.  One scene of three men in a foxhole was accompanied by a picture and a letter: the life-sized model recreated the photograph, and one of the veterans who was in the picture had written in the 80s to describe the experience. It was a moving letter, and helped me to really connect to what this was all about, and to give me a way of seeing into the scenes and the times.

One scene of three men in a foxhole was accompanied by a picture and a letter: the life-sized model recreated the photograph, and one of the veterans who was in the picture had written in the 80s to describe the experience. It was a moving letter, and helped me to really connect to what this was all about, and to give me a way of seeing into the scenes and the times.

There are dozens of everyday scenes,  soldiers struggling to move supplies through deep snow, a communications team huddled in a ruined basement, a mortar squad hiding in a farmhouse kitchen, troops lined up for a

soldiers struggling to move supplies through deep snow, a communications team huddled in a ruined basement, a mortar squad hiding in a farmhouse kitchen, troops lined up for a  rare hot meal, others searching for supplies in a town. The conditions were extreme that winter, and the abundant letters and photographs that line the walls describe the hardships of the battle and inadequacies of the food and clothing.

rare hot meal, others searching for supplies in a town. The conditions were extreme that winter, and the abundant letters and photographs that line the walls describe the hardships of the battle and inadequacies of the food and clothing.

It seem incredible that, within decades, Europeans were able to set the experience aside and come together as allies.

In Arnhem, in Diekirch, in Normandy, and elsewhere, I’ve visited battlefields and museums that vividly describe the fierce battles, sacrifices, and privation of that time. Smaller countries like the Netherlands and Luxembourg were occupied early in the war, and liberated later, so they don’t enter into our history texts as clearly. But a visit to these areas reveals the forced conscription, the raids on houses already short of food, the separation of families, and the harsh conditions that people endured for years. The experiences must have changed people, angered them, hardened them. Yet politically, and to a lesser extent socially, Europe seems to have been able to move past it.

I talked with some friends about why: maybe it’s because the Allies ultimately won the war, or because the generation that fought it has passed. Perhaps, as buildings are reconstructed and forests grow back, life returns. But active memories of conflicts last generations in other parts of the world, with endless wars of redress and revenge.

I haven’t found a satisfactory answer to how Europeans moved their lives past the scenes depicted in the museum. The vibrant city life outside shows that, however they did it, they made the right choices to leave a better world to their children. But I can’t imagine how.