Breakfast is not the morning mainstay that begins the day in Marrakech. The meal is a light combination of fruit, bread, and filled pancakes, honey and sliced cakes. Coffee is difficult to find before 8 am, and arrives as a cup pre-filled with warm milk accompanied by a small side serving of strong coffee.

Breakfast is not the morning mainstay that begins the day in Marrakech. The meal is a light combination of fruit, bread, and filled pancakes, honey and sliced cakes. Coffee is difficult to find before 8 am, and arrives as a cup pre-filled with warm milk accompanied by a small side serving of strong coffee.

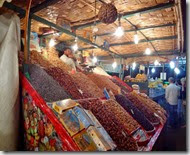

As a result, the day is a series of nibbles, stops for coffee or water, a sampling of almond cookies, soup and bread. I liked Harira, a tomato soup with lentils, and Khobz, a flat white bread that you break apart and dip.  I had planned to try Pastilla, a pastry shell stuffed with spiced squab, but the local restaurants all substituted chicken and there were too many other authentic choices to try.

I had planned to try Pastilla, a pastry shell stuffed with spiced squab, but the local restaurants all substituted chicken and there were too many other authentic choices to try.

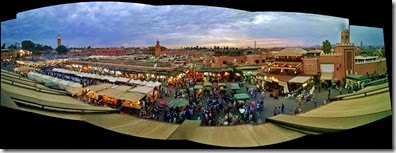

Fifteen minutes walk from the hotel is the Jamaa El-Fna, a vast paved plaza at the center of Marrakech, surrounded by terrace restaurants and pocket shops. By day, it has rows of souvenir stands and knots or people around snake charmers and street performers. It’s fun to wander, looking for a bargain or nibbling figs and apricots, but the square was usually just a touchstone to aid navigation among the palaces and museums.

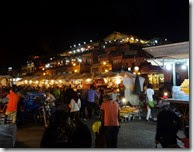

In early evening, we’d climb to one of the terraces and pay the obligatory drink fee for a table along the railing where we could sip ‘Moroccan whisky’ (mint tea) and watch the transformation that takes place below.

Just before sunset, fleets of trucks begin to unload long trestles which are quickly covered in white tablecloths Grills and braziers are set up and food is arranged in 100 separate stalls competing for the dinner trade. The lights come on beneath the tents as the sun sets behind the Koutoubia Mosque; people stream into the square from every direction.

In an hour, the square becomes a vast open-air food festival, brilliantly lit.

From ground level, it’s an amazing variety and opportunity:

The restaurants are flanked by orange juice stands (4 dirham a glass, but quick to swap to red grapefruit (a dead ringer for blood orange) for 20 dirham (2 euros) if they can).

The next row holds pots of winkles, smiling cooks slicing their arms down to invite passer-by’s to a stool. The snails aren’t garlic like the French escargot, but a lighter spice with a tea-flavoured broth that you drink afterwards (supposed to combat colds).

Then it’s time to plunge into the food vendors. Each stall has boys with menus who assure you that their cooks are the best, their meat is the freshest, their spices the most authentic. Hey Einstein, I remember you, you promised to come back, they would call on seeing my hair, pushing a menu into my hands. Tagines, Couscous, Kebabs, salads, fish, sausages and soups.

As with any restaurant search, I look for the eating spots that are filled with people, and that are populated by locals. Sometimes that led to stalls serving more traditional sheep’s head, so I had to dial back my rules a bit. But the best stalls were still the ones with truly Moroccan clientele. The w.wezen ran effective filtering and interference.

Things would start with a dish of tomato pesto and a spinach / onion mix, dabbed up with pieces of bread. The grilled aubergine was good, as were the soups. Many mains were built on couscous: I was particularly fond of the Merguez sausages. The tagine came up a bit short, mainly because I wasn’t used to mutton, mostly fat, distinct here from lamb.

After settling the bill (usually bearing little relation to the menu prices and about the standard 20 dirham over what I expected), it would be off for almond cookies and mint tea.

The markets stay open late, the stalls brightly lit and filled with lookers. Since alcohol is not served outside of hotels and a few restaurants, the crowd feels more purposeful and relaxed.

I never went to any of the main restaurants ringing the Jamaa, there was infinite variety and local authenticity beneath the food tents. Alfresco dining along the streets, communal amidst the cooks. ingredients, and the flow of people alongside the tables, was the only way to dine in Marrakech.

And I always got enough to see me past the next breakfast.