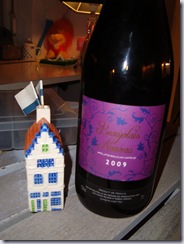

The nouvelle beaujolais hit the stores here in the Netherlands this week, 4 euro a bottle. The price is right, even if I don’t know what I’m buying. It’s the first sample of the vintage that will become 2009 and, although it’s taste will be raw and meaningless, there is some continuity from young to old that makes it worth a try.

Especially in this year, with so many new seeds planted in my life that it almost seems fitting to pause and give thanks for the hopes that may, finally, come to fruition in the years to come.

———————————-

A fellow blogger is off to participate in a pre-meeting ahead of the climate change summit in Copenhagen. He has good observations about the evidence for change, and I hope that he is successful in bringing these points forward.

Effective solutions are hard to come by, and failure is often blamed on social factors and political divisions. In the US, in particular, this has become a “red-blue” litmus issue. But I think that there is an economic side to the stalemate, one that engulfs more than the global warming issue.

I think that the pervasive economic belief in efficient free markets as solutions to social problems actually creates a lot of the difficulty that we have in solving large problems today. There is a religion in some quarters that worships global capitalism: problems are solved when production meets demand and to adapts to resources; costs and profits define the best solutions within these constraints.

Thus, climate change, health care reform, the banking crisis, all meet cries for less, rather than more, regulation, for unleashing innovation and energy through private initiatives, and for global free trade in resources to keep costs low. Opponents are forced to argue that government regulation, whether cap and trade, a public insurance option, or stronger monetary oversight, will somehow be wiser and more efficient than collective entrepreneurs.

I believe in the virtues of free-market entrepreneurship, but it’s efficiencies decline when markets and processes are dominated by companies that have become too big to fail, have monopoly influence over politicians and markets, profit by financial engineering, or expand by acquisition rather than the hard work of building a real competitive position.

My suggestion would be that these excesses should be more generally curbed through regulation so that a truly competitive landscape emerges. Then we might successfully harness individual creativity to find answers, backed up by seed funding and a public option for ‘last resort’ action that assures private initiatives aren’t left to themselves.