Georgia O’Keefe is an iconic twentieth century American artist, whose paintings are instantly and uniquely recognizable. Robert Hughes characterized her as “a ‘natural’: not a naive or primitive painter by any means, but one who seemed to be instinctively in touch with the vibrations of the cosmos.” I’ve visited her museum in Santa Fe, filled with simple, bold depictions of sensualized flowers, bleached bones and southwest landscapes.

Georgia O’Keefe is an iconic twentieth century American artist, whose paintings are instantly and uniquely recognizable. Robert Hughes characterized her as “a ‘natural’: not a naive or primitive painter by any means, but one who seemed to be instinctively in touch with the vibrations of the cosmos.” I’ve visited her museum in Santa Fe, filled with simple, bold depictions of sensualized flowers, bleached bones and southwest landscapes.

The Tate Modern is hosting a retrospective of  her work, on view through the end of October. It’s themed as ‘A century of O’Keefe’, celebrating 100 years since her first gallery showing. We spent a couple of hours exploring the thirteen rooms, nice for not focusing on the expected canvases. Although there were a few of her recognizable blooms, most of the exhibition has early works that anticipate the well-known paintings, showing how her methods and vision developed in the early decades of her work.

her work, on view through the end of October. It’s themed as ‘A century of O’Keefe’, celebrating 100 years since her first gallery showing. We spent a couple of hours exploring the thirteen rooms, nice for not focusing on the expected canvases. Although there were a few of her recognizable blooms, most of the exhibition has early works that anticipate the well-known paintings, showing how her methods and vision developed in the early decades of her work.

It also holds a number of photographs by her husband,

Alfred Stieglitz, that range from insightful (the portrait of her hands, above) to embarrassing (I can imagine him reassuring her that nobody would ever see the bedroom photographs as they were being taken).

I really liked her early abstract work in charcoal. When I took still-life classes, they were very geometric exercises, gridding off spaces and squaring off angles. Life drawing, in contrast, was all arcs and curves and living shadows: infinitely more appealing. I see that feeling in works like No. 12 Special, right.

I really liked her early abstract work in charcoal. When I took still-life classes, they were very geometric exercises, gridding off spaces and squaring off angles. Life drawing, in contrast, was all arcs and curves and living shadows: infinitely more appealing. I see that feeling in works like No. 12 Special, right.

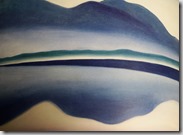

The organic exploration of edge, contrast and shadow continued through her early watercolours (Pink and Blue Mouuntain) and oils (Abstraction Blue), which almost foreshadow later flowers. Abstraction – Alexius and Grey Lines with Black, Blue and Yellow were also really striking close up.

The early landscape paintings were nighttime urban canyons , New York rather than Santa Fe. The liquid clouds and reflections of the moon in the lights are a nice unifying feature, repeated as she works through the ideas.

The realism gave way to full abstraction, soft and pillow-y, full of currents and storms.

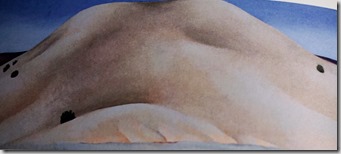

And it’s easy to see it all coming together as she discovered the desert Southwest.

It’s a lovely show to spend time browsing the works, connecting the styles, and reflecting on her career. And, in the end, I didn’t really miss the flowers.

‘a bit like seeing beyond the wall of yellow sunflowers in the van Gogh museum as well